Overview of T-cell therapies for solid tumors

Immunotherapy is designed to activate or boost the immune system’s ability to identify and destroy cancer cells1

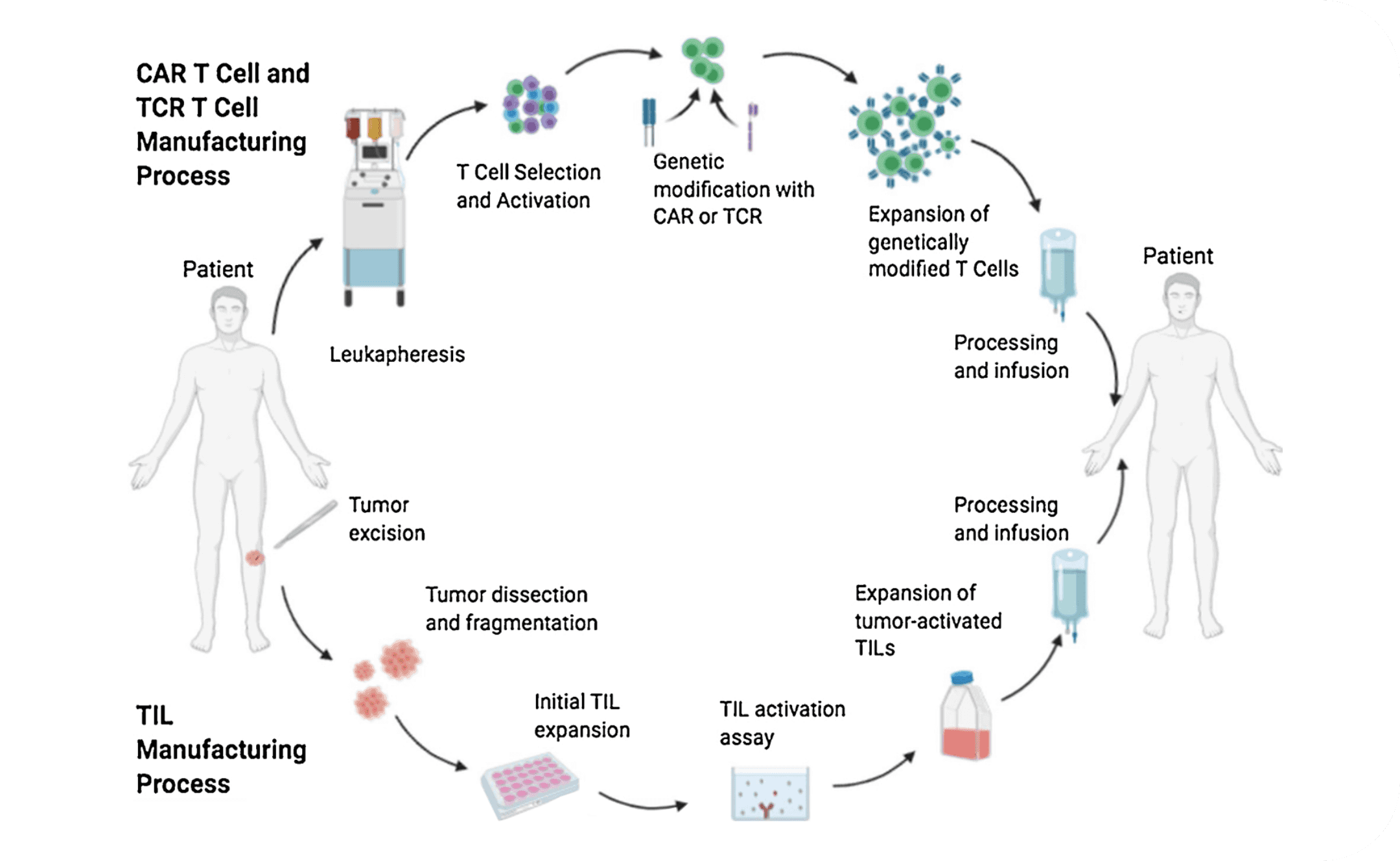

Autologous T-cell immunotherapy approaches involve removing a patient’s T cells, manipulating them ex vivo, and reinfusing the potentiated cells into the patient.2,3 While mechanisms and manufacturing processes may be unique to each type of T-cell immunotherapy, a shared foundation exists. T-cell immunotherapies typically involve:

- Collection of blood or fresh tumor4

- Isolation of T cells from these tissues4

- Growth and expansion phase to allow for T-cell proliferation4,5

- Lymphodepletion chemotherapy4

- Intravenous (IV) infusion of manufactured T cells4

- Immediate monitoring and close observation after infusion for acute toxicities6,7

- Long-term safety follow-up8

The most common types of T-cell immunotherapies currently approved for use or in late-stage clinical development use chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T cells, T-cell receptor (TCR) T cells, and tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes (TILs)4

Autologous CAR T-cell therapy: advancing care in hematologic malignancies10

T cells can be redirected to tumor cells by genetically adding a CAR that is specific to an antigen expressed on the surface of the tumor cells, leading to enhanced tumor cell killing.11,12 CAR T-cell therapy has shown promising efficacy in patients with hematologic malignancies, generating excitement in the field and propelling research into other cell therapy approaches.10 Depending on the frequency of the tumor antigen expression, prescreening for the CAR-directed target antigen may or may not be required.13,14 CAR T-cell therapies are being used for the treatment of hematologic malignancies, but are not currently approved for use in solid tumors.10

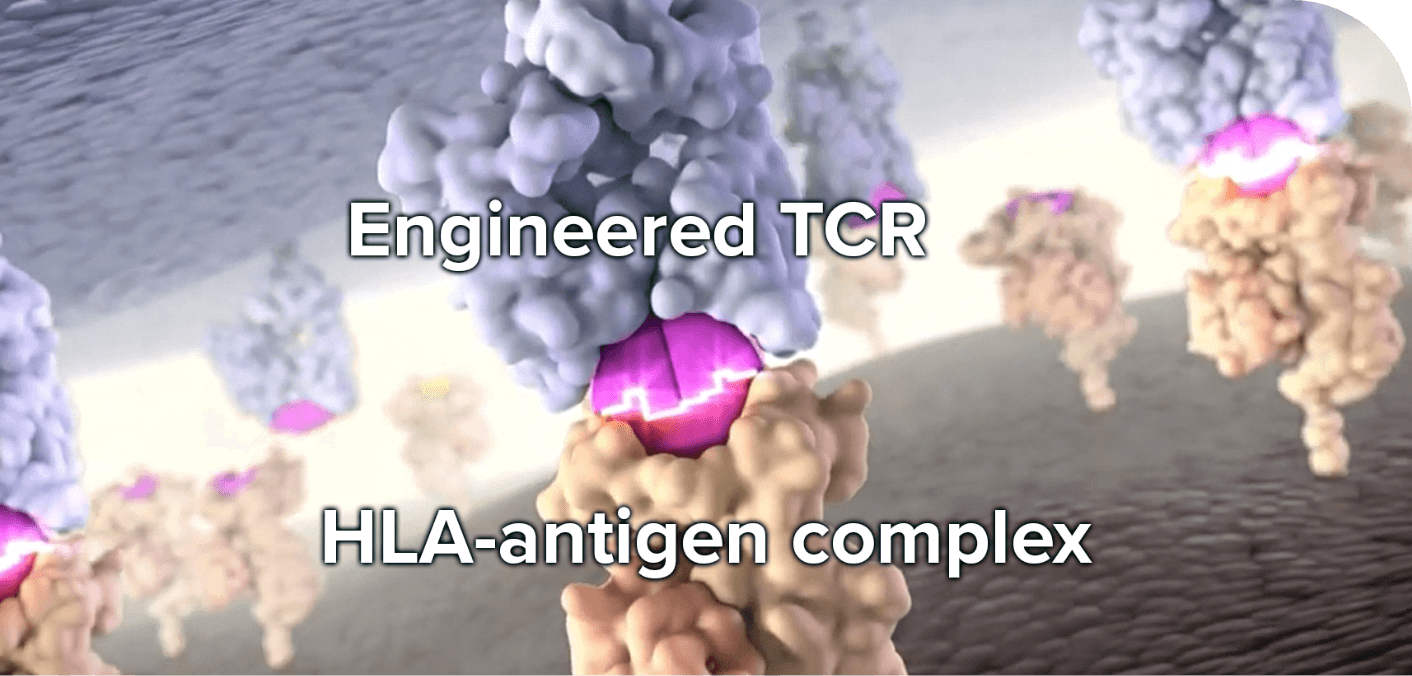

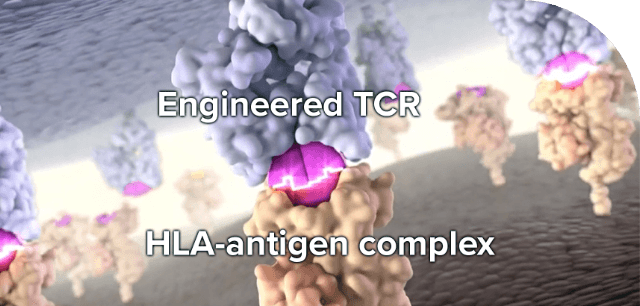

Autologous TCR T-cell therapy: personalizing medicine further11

TCR specificity is responsible for maintaining a distinction between self and nonself (eg, tumor cells). TCR T-cell therapy takes advantage of this specificity to target and selectively kill cancer cells.10,15 Tumor cells express fragments of tumor antigens (peptides) complexed with class I or II HLA on their cell surface. This unique complex is what the engineered TCR recognizes and binds to.10,16 Therefore, patient-specific identification of both HLA type and tumor antigen expression is required for some types of TCR T-cell therapies undergoing continued research to provide this type of tumor-selective, patient-personalized therapy.11

Most TCR T-cell immunotherapies in clinical development are HLA dependent and will, thus, require identification of HLA subtypes for patient eligibility. HLA-independent TCRs are also under investigation in clinical trials.11,17,18

CAR and TCR T-cell therapy

There are a few key attributes that differentiate CAR T-cell therapies and TCR T-cell therapies.11

Autologous TIL therapy: Exploring an alternate approach22

T cells commonly infiltrate solid tumors.22 However, they are often ineffective at killing tumor cells due to the immunosuppressive tumor microenvironment.3 For TIL immunotherapies, fresh tumor samples are typically collected by biopsy or surgical procedure to obtain TILs from the patient.23 The TILs are not genetically modified or engineered but only activated and expanded.24 Since TILs are isolated from a patient’s tumor, prescreening for specific biomarkers is not usually necessary.3,24,25

Next

Role of T-cell receptors

References

- Riley RS, June CH, Langer R, Mitchell MJ. Delivery technologies for cancer immunotherapy. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2019;18(3):175-196.

- Stanculeanu DL, Daniela Z, Lazescu A, Bunghez R, Anghel R. Development of new immunotherapy treatments in different cancer types. J Med Life. 2016;9(3):240-248.

- Qin SS, Melucci AD, Chacon AC, Prieto PA. Adoptive T cell therapy for solid tumors: pathway to personalized standard of care. Cells. 2021;10(4):808.

- Rohaan MW, Wilgenhof S, Haanen JBAG. Adoptive cellular therapies: the current landscape. Virchows Arch. 2019;474(4):449-461.

- Milone MC, Bhoj VG. The pharmacology of T cell therapies. Mol Ther Methods Clin Dev. 2018;8:210-221.

- Dana-Farber Cancer Institute. How CAR T-cell therapy works. Accessed October 4, 2023. https://www.dana-farber.org/cellular-therapies-program/car-t-cell-therapy/how-car-t-cell-therapy-works/

- Boldt C. TIL therapy: 6 things to know. MD Anderson. April 15, 2021. Accessed September 19, 2023. https://www.mdanderson.org/cancerwise/what-is-tumor-infiltrating-lymphocyte-til-therapy--6-things-to-know.h00-159460056.html

- US Food and Drug Administration. Long Term Follow-Up After Administration of Human Gene Therapy Products: Guidance for Industry. January 2020. Accessed September 19, 2023. https://www.fda.gov/media/113768/download

- Grimes JM, Carvajal RD, Muranski P, et al. Cellular therapy for the treatment of solid tumors. Transfus Apher Sci. 2021;60(1):103056.

- Zhang J, Wang L. The emerging world of TCR-T cell trials against cancer: a systematic review. Technol Cancer Res Treat. 2019;18:1533033819831068.

- Tsimberidou AM, Van Morris K, Vo HH, et al. T-cell receptor-based therapy: an innovative therapeutic approach for solid tumors. J Hematol Oncol. 2021;14(1):102.

- June CH, Sadelain M. Chimeric antigen receptor therapy. N Engl J Med. 2018;379(1):64-73.

- Frigault MJ, Bishop MR, O'Donnell EK, et al. Phase 1 study of CART-ddBCMA, a CAR-T therapy utilizing a novel synthetic binding domain for the treatment of subjects with relapsed and refractory multiple myeloma. Blood. 2020;136(suppl 1):653.

- Mirzaei HR, Rodriguez A, Shepphird J, Brown CE, Badie B. Chimeric antigen receptors T cell therapy in solid tumor: challenges and clinical applications. Front Immunol. 2017;8:1850.

- Crux NB, Elahi S. Human leukocyte antigen (HLA) and immune regulation: how do classical and non-classical HLA alleles modulate immune response to human immunodeficiency virus and hepatitis C virus infections? Front Immunol. 2017;8:832.

- Baulu E, Gardet C, Chuvin N, Depil S. TCR-engineered T cell therapy in solid tumors: state of the art and perspectives. Sci Adv. 2023;9(7):eadf3700.

- Hassan R, Butler M, O’Cearbhaill RE, et al. Mesothelin-targeting T cell receptor fusion construct cell therapy in refractory solid tumors: phase 1/2 trial interim results. Nat Med. 2023;29(8):2099-2109.

- Liu Y, Yan X, Zhang F, et al. TCR-T immunotherapy: the challenges and solutions. Front Oncol. 2022;11:794183.

- Salter AI, Rajan A, Kennedy JJ, et al. Comparative analysis of TCR and CAR signaling informs CAR designs with superior antigen sensitivity and in vivo function. Sci Signal. 2021;14(697):eabe2606.

- Poorebrahim M, Mohammadkhani N, Mahmoudi R, Gholizadeh M, Fakhr E, Cid-Arregui A. TCR-like CARs and TCR-CARs targeting neoepitopes: an emerging potential. Cancer Gene Ther. 2021;28(6):581-589.

- Harris DT, Kranz DM. Adoptive T cell therapies: a comparison of T cell receptors and chimeric antigen receptors. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2016;37(3):220-230.

- Zikich D, Schachter J, Besser MJ. Predictors of tumor-infiltrating lymphocyte efficacy in melanoma. Immunotherapy. 2016;8(1):35-43.

- Jiménez-Reinoso A, Nehme-Álvarez D, Domínguez-Alonso C, Álvarez-Vallina L. Synthetic TILs: engineered tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes with improved therapeutic potential. Front Oncol. 2021;10:593848.

- Wu R, Forget MA, Chacon J, et al. Adoptive T-cell therapy using autologous tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes for metastatic melanoma: current status and future outlook. Cancer J. 2012;18(2):160-175.

- Chandran SS, Somerville RPT, Yang JC, et al. Treatment of metastatic uveal melanoma with adoptive transfer of tumour-infiltrating lymphocytes: a single-centre, two-stage, single-arm, phase 2 study. Lancet Oncol. 2017;18(6):792-802.